Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Clinton’s British forces evacuated Philadelphia on 18 June 1778, after a nine-month occupation. Brigadier General William Maxwell’s four New Jersey regiments were already in their home state, positioned to observe the British army and oppose any overland move towards the coast. Clinton’s columns commenced their march towards New York on June 18th, and New Jersey Continentals and militia immediately began operations to impede the movement. The 20 to 27 June harassment operations caused more casualties in the New Jersey Brigade than the campaign’s culminating battle. Acting most often in small parties, usually in conjunction with militia, the four Jersey regiments suffered two killed, an additional death possibly of sunstroke, five wounded, nine captured, and one missing. In contrast, Maxwell’s brigade casualties in the 28 June battle were seven (possibly eight) wounded and four missing. General George Washington’s Monmouth battle losses were 224 killed and wounded; 132 men were also listed as missing, but an appended casualty note stated “Many of the missing dropt thro’ fatigue and have since come in -“1

The Monmouth battle itself was a confused affair and only recently have serious efforts been made to make sense of the day’s events. The purpose of this treatise is to gain some understanding of the New Jersey troops' experiences on that hot June day, and to give context to those experiences by providing integrated primary accounts of the entire battle and its aftermath. The following narrative is based on the proceedings of Major General Charles Lee's court martial (July and August 1778), and Colonel Henry Jackson's court of inquiry (April to July 1779), interwoven with soldiers’ letters, diary excerpts, and pension depositions. I recommend the Lee court martial transcript as invaluable, interesting, and enlightening to those hardy souls willing to wade through the daunting mass of depositions. Evidence of problems in command control and moving troops in the field, as well as personality conflicts, bickering, and conflicting testimony, are all contained therein.

Appendices containing longer or unedited primary documents and special studies relating to the Monmouth Campaign and the New Jersey Brigade accompany this work.

Two maps, one showing the British and American routes from Philadelphia and Valley Forge to Monmouth, and the other showing the place names on the battlefield are available to the reader. These open in a separate window and allow viewing the map without losing your place in the text. Links are provided in the narrative to open these resources.

[New Jersey officers’ and soldiers’ narratives; info. on New Jersey artillery.]

* * * * * * * * * * * *

Continental soldier in hunting shirt and overalls, preferred wear for warm weather service. Peter F. Copeland (artist) and Donald W. Holst, Brother Jonathan print series. Courtesy of the artist.

"In readiness to march at a moment's

warning ...":

Pre‑Battle Dispositions and Plans

[Narratives of British and American march to Monmouth]

[Studies of Monmouth Campaign shelter, and American clothing and food]

Many soldiers left accounts of the train of events preceding the June 28th Monmouth battle. Perhaps the best for our purposes is Henry Dearborn’s journal narrative. Dearborn, lieutenant colonel of the 3rd New Hampshire Regiment, marched with General George Washington’s main army from Valley Forge, and was assigned to Brigadier-General Charles Scott’s light troops on 24 June. Brigadier- General William Maxwell’s New Jersey Brigade worked closely with Scott’s detachment during the advance to Monmouth Courthouse on the morning of 28 June, and in many ways the two commands had similar experiences. One great difference was that the New Jersey regiments were not at Valley Forge when the campaign began, instead opposing the Crown forces movement from its beginning at Cooper’s Ferry, New Jersey. Colonel Dearborn begins by recounting the Continental Army departure from Valley Forge. Route map

17 [June, Valley Forge camp] we hear that the Enimy are Crossing the River over into the Jerseys -

18 this four noon we are Assured that the Enimy have Lift Philadelphia & our advanced Parties have taken Possession. Genrl. Lees Division is ordered to march Immediately for Corells ferry. At 3 O Clock we march.

After crossing the Delaware River at Coryell’s Ferry, and moving on to Hopewell, New Jersey, the army halted till the 25th. Dearborn’s account continues:

24th a Detatchment of 1500 Pick’d men was taken to Day from the army to be Commanded by Brigadier Genrl. Scot who are to act as Light Ingantry … Colo. Cilley & I am in one Regt. of the Light Infantry - Genrl. Scot march’d to Day towards the Enimy, who are at Allin Town … we march’d thro Prince Town & Proceeded 3 miles towards allin Town & Incamp’d

25th this morning we march.d within 5 miles of the Enimy - & Halted & Drew Provision. Sent a small Party of Horse to Reconoightir the Enimy. At 12 O Clock we ware Inform.d that the Enimy ware on their way to Monmouth Coart House. Which is Towards Sandy Hoock. Our main army is Near Prince Town, we are now Prepared to Harress the Enimy. Genrl. Scot 1500 men Genrl. Maxwell 1000 Colo. Morgan 500 - Genrl. Dickerson 1000 [New Jersey] Millitia; & 200 Horse. the above Detatchmts are on the Flanks and Rear of the Enimy … at 4 O Clock P:M we marchd to Allin Town & Incamp.d. - the Enimys Rear is 5 miles from us -

26th we march’d Early this Morning after the Enimy. The weather is Extreemly Hot, we are Obliged to march very Modirate … we are Join’d to Day by the Marquis De lefiette with a Detatchment of 1000 men. We advanced within three miles of the Enimy, & Incamp’d. the Enimy are about Monmouth Court House, on good Ground -

27th we march.d Early this morning within one mile of the Enimy & ware ordered by an Express from Genrl. Washington to Counter March to where we Incamp’d Last night, & from thence to file off to English Town (which Lay 7 miles on Our Left as we followed the Enimy) & their Join Genrl. Lee Who was there with 2000 men. the weather Remains Exceeding Hot & water is scarce we ariv.d at English Town about the middle of the Day & Incamp’d. the Enimy Remain at Monmouth. Genrl. Washington with the Grand army Lays about 5 mile in our Rear. Deserters come in in Large numbers.2

Captain Jonathan Forman, 4th New Jersey Regiment, recorded meeting Scott’s troops and subsequent movements, “the 25.th. Ab.t 4 O.Clk in the Aftrnoon Marchd to Heights Tn.o where we were Join.d by G[eneral]. Sc[o]tts Light Troops and the Marquis [de Lafayette] Continuing to keep on the E[nemy's]. left. 26[th] March.d to Robins[']s tavern the En[em].y Moving towards Monmouth | 27.th began our March Early in the Morning March.d to English Tn.o Gen.l Scott march[in].g in the rear of the Enemy Near burnt Tav.n then moving by the left Joined us up wth at English Tn.o where we were Joined by a part of the main Army.” First Jersey Regiment Colonel Mathias Odgen later recalled, "General Maxwell's brigade... together with General Scott's and General Wayne's detachments, lay at the Sun‑Tavern, about five or six miles from Allen‑Town, on the Monmouth Court‑house road, when we received orders to join General Lee at English‑Town. We joined General Lee the 27th." New Jersey militia Colonel Sylvanus Seely noted the same day, “marched to a meeting house near English Town; our men suffered greatly with heat and drought. Was sent in the evening with 200 men to keep a guard at Mills and the enemy had a party there who had taken and killed a scouting party of our light Infantry but on our appearing they left the ground and we took possession and stayed all night.”3

On the night of 27 June General Washington met with Major-General Charles Lee and his advance force commanders. Brigadier-General Anthony Wayne remembered that he "did not hear General Washington give any particular orders for the attack, but he recommended that ... in case of an attack, that as General Maxwell was the oldest, he of right would have the preference, but that the troops that were under his command, were mostly new levies, and therefore not the proper troops to bring on the attack; he therefore wished that the attack might be commenced by one of the picked corps, as it would probably give a very happy impression." General Maxwell himself stated that during the meeting the commander in chief "said to General Lee, that General Lee was to attack the rear of the British army as soon as he had information that the front was in motion or had marched off; General Washington further mentioned, that something might be done by giving them a very brisk charge by some of the best troops ... [he] mentioned something about my troops, that some of them were new, and the want of cartouch boxes, and seemed to intimate that there were some troops fitter to make a charge than them." While the New Jersey general may have wished to lead the attack he could not reasonably argue with General Washington's assessment of his brigade, thirty‑nine percent of which was comprised of new levies (i.e., men drafted from the state militia to serve in the Continental regiments for nine months); Maxwell’s New Jersey regiments were in fact the only units in Lee’s advance force with significant numbers of drafted men. As events unfolded, the New Jersey regiments marched in the rear of Lee’s column the following day.4

* * * * * * * * * * * *

"To get up with the enemy"

Lee's Force Sets Off

[Appendix C - Lee's Force Order of Battle. ]

Early the next day Lee's troops marched towards Monmouth Court House. Bernardus Swartout, a volunteer with the 2nd New York Regiment, noted the departure from a common soldier’s vantage point, “28th. We drew rum & provisions - were ordered to march - not having time to prepare our provisions or eating - left our baggage of every kind behind, also the soldiers coats.” Lt. Col. John Brooks, Lee’s adjutant, stated that "At about ... [6 o'clock in the morning] General Lee sent me with orders to the several detachments and Maxwell's brigade, to prepare for marching immediately, leaving their packs behind under proper guard ..." Brooks also recalled the advanced detachment’s strength and the state of their encampment after the column stepped off: "General Scott's detachment ... consisted of about fourteen hundred and forty; General Wayne's of one thousand, General Maxwell's brigade, as he told me, of nine hundred, Varnum's brigade of a little better than three hundred ... Scott's brigade was less than three hundred, Jackson's detachment of two hundred. When [they] marched from English‑town [General Lee] ordered all the packs to be left, under the care of proper guards. After the troops had paraded to march at English‑town, I rode through the different encampments and found the baggage very strongly guarded. Upon riding up to several and enquiring the reason of so many men being there, I was answered in general that they were men who were lame, sick, and those who were worn out with the march the day before, together with the guards who were left with the baggage. The idea that I then formed of those left on the ground was, that they were between four and five hundred in the whole."5

In his recounting General Maxwell stated that during the 27 June evening meeting "General Washington ... recommended that we should go to General Lee's quarters, at six o'clock [next morning]; the orders I got there were to keep in readiness to march at a moment's warning, in case the enemy should march off ... In the morning of the 28th, I think after five o'clock, I received orders from General Lee to put my brigade in readiness to march immediately; I ordered the brigade to be ready to march, and went and waited on General Lee; he seemed to be surprized that I was not marched, and ... informed me, some were already marched, and that I must stay 'till the last and fall in the rear. I ordered my brigade immediately to the ground I understood I was to march by, and found myself to be both before General Wayne and General Scott, and halted my brigade to fall in the rear: when about one half of the troops were by, orders came ... to march my brigade by the road towards Craig's mill, 'till I met with the first direct road that led away to the Court‑house, and to halt there until further orders, as it was suspected that the enemy were moving some part of their troops that way. By the time I had got about half a mile towards that place, one of General Washington's Aids gave orders to the rear of the brigade ... to return to my old ground, and that the front of the enemy was certainly marched off ... which I did. I came back to my former station, and waited there a considerable time before General Wayne and General Scott's troops got past me; then I marched in the rear; there were three pretty large halts made before I got up within a mile of the Court‑house." Colonel Matthias Ogden, 1st New Jersey, stated that after the "order was countermanded … we were ordered to join the troops that had gone towards the Court‑house ... [which was effected] at or near Freehold Meeting‑house [Tennent Church] ..." General Scott, whose brigade marched immediately in front of the New Jersey troops recalled that "we marched on near the [Tennent] Meeting‑house, where there was a ... halt made ... [after a short time] we were again ordered to march on ..."6

Captain John Mercer, aide-de-camp to General Lee, also described the morning march.

I don't conceive that the troops were ready before eight o'clock or half past eight, at which time General Lee set out from his quarters. We past the troops, who were about one‑quarter of a mile advanced of English‑town, on the Freehold road, and then on their march ... [after receiving intelligence that the enemy] had arranged their whole army at Freehold ... [and that they] would throw a column on the Covenhoven road, which led from Freehold into the rear of our position at English‑town ... he then rode on himself, and expressed a good deal of uneasiness at the party under Colonel [William] Grayson, who had some time before been ordered to quicken their pace, if possible, to get up with the enemy; he desired me to ride back and beg of General Wayne that he would come forward and take command of those advanced troops, as he looked upon it as a post of honour; and likewise to order General Maxwell's brigade, which General Lee ... had ordered to march in the rear of the troops, into the Covenhoven road, to march to the forks of that road, where a road led from Craig's mill to the Court‑house; to take a position there for his brigade, and wait either the enemy or for further orders. I executed both of these orders, [and] delivered General Maxwell a rough draught of the road ... [a short time later I] met with Colonel [Richard Kidder] Meade [commander in chief’s aide], who told me he was going back with General Lee's order to bring on the troops; I begged of him to ride to General Maxwell's brigade, who could not have marched far, and order them back again. I then made what haste I could to General Lee; I overtook him on the other side of the bridge, in front of the position [Continental Army Major-General William Alexander] Lord Stirling afterwards took ... not a man of General Lee's command had arrived, or did arrive for three‑quarters of an hour, at that place, except the command of Colonel Grayson ... [Shortly after this Mercer, hearing the enemy was in the rear left] was sent off with Varnum’s brigade … I got to the orchard, where I found them to be a large body of [New Jersey] militia, who had lost themselves, under the command of Colonel Freylinghausen. I immediately returned … By this time, the head of the column under the Marquis de la Fayette, had got in view, and the General immediately ordered the troops on, having before dispatched orders to bring on Colonel [Richard] Butler's [9th Pennsylvania] and Colonel [Henry] Jackson's regiments to form the advance guard; they got up and were formed, and the General proceeded on with them to the front, without making any kind of halt, until we got in sight of the Court‑house.7

Earlier in the day Lt. Col. Jeremiah Olney, 2nd Rhode Island Regiment, witnessed the battle’s opening skirmish: “on the morning of the 28th of June … as Generals Scott and Varnum’s brigades, under the command of Major-General Lee, were advancing towards the enemy at Monmouth, after they had marched a half a mile below the Meeting-house, on the road leading to Monmouth, a small skirmish happened a little in front between the British horse [Hussars, Queen’s American Rangers] and [Hunterdon County] militia, in which the militia gave way …”8

* * * * * * * * * * * *

"I

found the whole of the troops upon my right retreating ..."

Morning

Confrontation at Monmouth Courthouse

Brigadier-General Scott noted that following a short halt at Tennent Meeting his detachment and Maxwell’s brigade, at the column’s rear, received orders to continue on. "About a mile beyond the Meeting‑house we were again halted some short time, when several pieces of cannon were fired, and some small arms in front of the column, about which time we were ordered on, and soon took a road leading us immediately to the left. After marching near one‑half a mile, we turned [on] an old road to our right, which brought us into a field to the left of some of our troops that were formed, where there was a pretty brisk fire of cannon on both sides." Adjutant John Brooks stated that once the rest of the American column entered the plain near Monmouth Court House he saw General Scott "and part of his troops in the wood" through which the van of Lee's force had just marched. "The head of the column at this time had arrived nearly in front of the orchard where Colonel [Eleazer] Oswald [2nd Continental Artillery] afterwards took his post. When I first came into the open ground I rode up to the point of the woods to take a view of the enemy ... [after approximately ten minutes I returned] and found the whole of, as I supposed, General Scott's detachment in the plain field to the right of the wood; his right battalion near the ravine and his left near the woods..." General Scott recounted, "I receiving no orders more than these, to follow General Wayne's detachment, they wheeled to the right, and moved on in a line with those troops I saw formed; before I had got far enough to wheel up my detachment, I found the whole of the troops upon my right retreating ..."9

General Maxwell described the New Jersey brigade's advance towards Monmouth Court House and the beginning of the retrograde movement. After the abortive march towards Craig's Mills

I came back to my former station ... waited [until] ... General Wayne and General Scott's troops got past me; then I marched in the rear [until] ... I got up within a mile of the Court‑house. At that place the Marquis de la Fayette came to me, told me it was General Lee's wish that we should keep as much in the woods as possible; and that as I had a small party of militia horse, desired that I would keep those horse pretty well out upon my right, to observe the motions of the enemy that they might not surprize us; I think it was there‑abouts that I heard some firing of cannon and small arms. The march was pretty rapid from that place, and I followed up General Scott until I got the front of my brigade in the clear ground. I found ... that the clear ground made an angle with a morass on my right, and a thick brush on my left. General Scott was formed in my front, in about one hundred yards; an orchard was in front of him, where I saw the enemy moving towards our right. I at the same time saw our troops on the right moving; some said that they were retreating; others, that they were only moving to the right to prevent the enemy's getting round them. I did expect that General Scott would have moved to the right, as there was a vacancy between him and the other troops, and would have given me an opportunity to form, but while I was riding up to him, I saw his troops turn about and form into columns, and General Scott coming to meet me. I think he told me our troops were retreating on the right, and we must get out of that place; that he desired his cannon might go along with me, as there was only one place to get out, he would cross over the morass to the right if he could; upon which I ordered my brigade to face to the right‑about, and march back. The reason of my marching back was, that if I did not get over a certain causeway before the enemy came down on the right, I should have been in danger of losing my cannon.10

Colonel Brooks recalled that after having observed the position of "General Scott's detachment in the plain field to the right of the wood" he suggested to "General Maxwell more than once, that the point of woods to his front was a very excellent post for him to take while the troops were passing that ravine, as the enemy would not push the rear of the troops who were passing it, while that ground was occupied by his brigade. At the same time, upon the Captain of his artillery [Thomas Randall] enquiring whether that ground was suitable for artillery, I observed to him that it would command the enemy partly in flank ..." This detachment, consisting of two field pieces from Colonel John Lamb's 2nd Continental Artillery, later formed part of a battery under Colonel Oswald, which took post on a hill a short distance to the rear, covering the retreat of Lee's forces.11

Major-General Lee and staff gave their views of the action on the right. Captain Mercer recalled advancing “until we got in sight of the Court‑house. Colonel Butler's regiment was then formed opposite to the cross‑road that led from Freehold to Amboy, and the other troops were ordered to face towards the Court‑house. The whole troops under General Lee’s command were then up; Butler’s and Jackson’s formed the advance guard, Scott’s and Varnum’s brigades marched in front, General Wayne’s detachment, General Scott’s detachment and General Maxwell’s brigade formed the line.” Major General Lee noted that the latter half of the advance was executed "with great rapidity 'till we emerged from the wood into the plain; the wood extended itself close on our left to a point about 300 yards distant ... Arriving in the plain, in view of the enemy, the following was the disposition of our troops: The whole column (Maxwell's brigade excepted) had crossed the great ravine, where I halted General Wayne's original detachment in order to form a right, and then myself filed off Scott's detachment to the point of wood I mentioned, to form a left ... The plain was extensive, and ... their force was considerably larger than I had been taught to expect; a column of artillery, with a strong covering party, both horse and foot, presented themselves, in the centre of the plain, another much larger appear'd directing their course towards the Court‑house on our right." Colonel Brooks recalled, "After having passed the woods and coming out into the plain, about a mile below the Court‑house, being at some little distance from the front, I observed the head of General Lee's column filing to the right towards the Court‑house. The whole of the column ... kept on in the same direction till the whole made a halt, which lasted about ten or fifteen minutes. A cannonade had now taken place between us and the enemy, who at this time appeared to be gaining the Court‑house and our right; at this time the column began its march, and I immediately rode to the left to see what position the troops were in.” After initial minor contact with the enemy General Wayne was ordered to "advance with the troops under his command [which consisted at this time of Colonel Henry Jackson's, Lt. Col. John Park's and Colonel Richard Butler's regiments] and attack the enemy in the rear; that all the General expected from his attack was, to halt the enemy ... [the aforesaid three regiments formed the left of the line and, after they came up,] The three regiments in General Wayne's [original] detachment, Colonel [James] Wesson's, Colonel [Walter] Stewart's, and Colonel [Henry] Livingston's, were ordered to the right, and General Lee rode out to reconnoitre the enemy, who now appeared in full view. He rode toward's Colonel Oswald's [two artillery] pieces, who had began a very sharp fire on the enemy, but a much severer was kept up from them, as they had a great many more pieces ... they appeared in much greater numbers I believe than General Lee expected ..." (Lt. Col. Alexander Hamilton wrote later, “I was spectator to Lt Col: Oswalds [2nd Continental Artillery] behaviour, who kept up a gallant fire from some pieces commanded by him, uncovered and unsupported …”) Captain Mercer blamed the premature withdrawal on Scott's detachment and Maxwell's brigade at the left of the line. After contact with the British near the Courthouse Wayne’s command was also forced to retreat, making their way back towards "the height occupied afterwards by Lord Stirling ..."12

The best, most comprehensive account of the morning maneuvers is provided by Lt. Col. John Laurens, a volunteer on Washington’s staff. He wrote to his father Henry, President of Congress:

The enemy’s rear was preparing to leave Monmouth village … when our advanced corps was marching towards them. The militia of the country kept up a random running fire with the Hessian Jagers [actually Queen’s American Rangers] no mischief was done on either side. I was with a small party of horse, reconnoitring the enemy, in an open space before Monmouth, when I perceived two parties of the enemy advancing by files in the woods on our right and left, with a view as I imagined, of enveloping our small party or preparing a way for a skirmish of their horse.13

In a 2 July letter Colonel Laurens explained, “Genl Steuben, his aids and your son, narrowly escaped being surrounded by the British horse, early on the morning of the action. We reconnoitred them rather too nearly, and Ld Cornwallis sent the dragoons of his guard to make us prisoners. [an attached notation states “A deserter from the enemy just informs us of this.”] Genl Clinton saw the Baron’s star, and the whole pursuit was directed at him; but we escaped, the dragoons fearing an ambuscade of infantry.”14 Laurens continues,

I immediately wrote an account of what I had seen to the General [Washington], and expressed my anxiety on account of the languid appearance of the continental troops under Genl Lee … [shortly after reporting to General Lee in person] I … returned to make further discoveries. I found that the two parties had been withdrawn from the wood, and that the enemy were preparing to leave Monmouth … Genl Lee at length gave orders to advance. The enemy were forming themselves on the Middle Town road, with their light infantry in front, and cavalry on the left flank, while a scattering, distant fire was commenced between our flanking parties and theirs. I was impatient and uneasy at seeing that no disposition was made, and endeavored to find out Genl Lee to inform him of what was doing … He told me that he was going to order some troops to march below the enemy and cut off their retreat. Two pieces of artillery were posted on our right without a single foot soldier to support them. Our men were formed piecemeal in front of the enemy, and there appeared no general plan or disposition calculated on that of the enemy … The enemy began a cannonade from two parts of their line; their whole body of horse made a furious charge upon a small party of our cavalry and dissipated them, and drove them till the appearance of our infantry and a judicious discharge or two of artillery made them retire precipitately [the only infantry action near the courthouse was one volley fired Butler’s 9th Pennsylvania Regiment at the 16th Light Dragoons]. Three regiments of ours that had advanced in a plain open country towards the enemy’s left flank, were ordered by Genl Lee to retire and occupy the village of Monmouth. They were no sooner formed there, than they were ordered to quit that post and gain the woods [behind them]. One order succeeded another with a rapidity and indecision calculated to ruin us. The enemy changed their front and were advancing towards us; our men were fatigued with the excessive heat. The artillery horses were not in condition to make a brisk retreat. A new position was ordered, but not generally communicated, for part of the troops were forming on the right of the ground, while others were marching away, and all the artillery driving off. The enemy, after a short halt, resumed their pursuit; no cannon was left to check their progress. A regiment was ordered to form behind a fence [Jackson’s Additional Regiment], and as speedily commanded to retire.15

Pennsylvania General Anthony Wayne more succinctly related the ignominious events to his wife, “On Sunday the 28th June our flying Army came in view of the Enemy about Eight O’Clock in the morning, when I was Ordered to Advance and Attack them with a few men - the Remainder of the Army under Genl Lee was to have Supported me - we accordingly Advanced - and Received a Charge from the British horse and Infantry, which we soon [Repulsed] - however our Genl thought Proper [to Retreat] in place of Advancing - without our firing a Single Shot …”16

Several other British and American soldiers left interesting accounts. Volunteer Bernardus Swartout, 2nd New York Regiment, wrote, “At 9 O.Clock A.M. fell in with the enemy at, or near, Monmouth Court House; we immediately formed in a field and a few cannon shots were exchanged - We not being posted in an advantageous position as Gen. Lee thought, were ordered to recross a defile or morass in our rear and form again in a wood - remained there an hour - The enemy advanced - Gen. Lee gave us orders to retreat (to the parties disatisfaction) from an advantageous piece of ground …” British Captain John Peebles, Grenadier Company, 42nd Regiment, related that “Between 9 & 10 oclock when our Brigade was about 4 miles advanced from the Village of Monmouth, (the Rear of the Division I suppose about 2 miles behind) the Enemy made their appearance in force near the Rear; the General rode back & ordered the troops to face about and march back with all speed to attack the Rebels; as our Troops approach’d their van, a Cannonade began about the East end of the Village, but the enemy soon retired to their more solid Column as the flank Corps moved up …” And Lieutenant William Hale, 45th Regiment Grenadier Company, claimed that “Lee, acquainted with the temper of our present Commander, laid a snare which perfectly succeeded. The hook was undisguised with a bait, but the impetuosity of Clinton swallowed it.” Hale went on to describe the events, “A few Light Troops began a desultory kind of attack on the flank of our rear guard, composed of the Grenadiers and Light Infantry and Rangers, in which the Rangers were chiefly engaged, and [Colonel] Simcoe received a flesh wound in the arm. Larger bodies were then seen quitting the woods, and filing off towards some heights in our rear, passing within cannon shot of our Battalion. Through my glass I plainly

saw from their variegated cloth[e]s they did not belong to our Army, but Col. [Henry] Monckton [commander 2nd Grenadier Battalion] asserted them to be provincial troops; fatally for him we were not long deceived, the firing became every moment hotter; several cannon shot were fired without effect, and the Grenadiers were ordered to the right about and march to the heights of which the Rebels were already possessed …”17

* * * * * * * * * * * *

"The

day was so excessively hot ..."

Lee’s

Retreat

During Charles Lee’s court martial there was conflicting testimony on a number of points, the most contentious issues being lack of clear command control, and why and where the American retreat began, issues evident in the previous section. General Lee’s staff officers Colonel John Brooks, and Captains John Mercer and Evan Edwards all agreed the rearward move began on the left with General Scott’s detachment; Generals Anthony Wayne and Charles Scott told the commander in chief in a joint letter two days after the battle that the retreat commenced on the right. These conflicts evidenced confusion on the field, as well as post-battle factional infighting. (Historian Garry Stone notes what actually occurred, “Scott moved back to the south bank of the ravine, sent Maxwell round to rejoin Lee in center … but they did not inform Lee. When Lee sent his aides to tell Scott to hold his position, all they found was a cloud of dust disappearing down the road (Maxwell’s rear). They informed Lee that Scott and Maxwell had taken French leave.”)18

General Maxwell recounted the events that began the withdrawal and the retreat itself. At the end of the morning’s march, he reported, the four New Jersey regiments "halted on the ground in the rear of General Scott... not ten minutes... [though] above five minutes; I think I had time enough to have formed there if there had been ground for it..." After this brief respite, Maxwell discussed the situation with Scott, then ordered his troops to retrace their steps. The Jersey Brigade commander noted,

When I came to the open ground, within sight of the [St. Peter’s] Church … I plainly saw our troops retreating on the right in several columns, and apparently to me in very good order. I then sent off my Quarter‑Master [Aaron Ogden] to General Lee, to know if he had any orders for me; at the same time my brigade was forming in the open ground by the woods, near the road I had gone up in. The Quarter‑Master … came back and told me that General Lee ordered me to throw my brigade over into the woods on the right. I was very angry at him, and thought he had not represented to the General where I was, or had not taken up the orders right, but he persisted in it. I did expect there that the whole of our troops would have halted, as General Lee had given orders to throw some troops into the woods on the right. I expected that I should have fallen into the woods on the left, and there was a commanding high ground there, where some of the pieces of cannon were halting, but I still saw the columns marching on, upon which I thought it my duty to keep on the left with them, and on an equal pace with them; but at the same time I rode off to General Lee, who I found in an orchard, near a house [the Rhea homestead], about a mile this side of Monmouth Court‑house, and asked him if he had any orders for me, or any directions to give me; he desired that I should throw my troops over on the right into the woods, and I thought still that he did not know my situation, and told him I was on the left, and it was out of my power, as the rest of the columns that were coming up would break them, and go through them; well, then, said he, stay on the side where you are. He first talked to me of stopping three regiments to cover three pieces of cannon that were there, but there seemed to be plenty of troops about them, and finally, we agreed that I should cross a defile and throw my troops into the woods upon the left, and to watch a road that led from Furman's mill [the fork in the road north of the point of woods-the left-hand fork leading past the Craig House to Forman’s Mills], which I did. The day was so excessively hot then, that the men were falling down; General Lee recommended that they might get water, and get among the bushes into the wood, that it might serve the purpose of sheltering the men and watching that road. While my brigade lay there, the rest of our troops were marching on, both to the right and to the left, crossing a defile that was in our rear. I rode out to the right, to observe what sort of ground was there, and to see if the enemy were coming up after us. Upon casting my eye over to where my brigade was, I saw them in full march out of the woods; I rode back as fast as possible, and desired to know by whose orders they marched out of the place I had stationed them; Colonel Shreve told me he received orders from a certain Major Wikoff, who, he said, the Marquis de la Fayette had ordered to go and forward all the troops over that defile, that was in our rear; not being pleased with it, I halted the brigade some time, and then I thought proper to let Colonel Shreve pass over the defile with the cannon, which he did, and took place on the other side with his cannon, in the edge of the woods, a place which seemed suitable to cover that defile, and I shortly after ordered over the other two of my regiments to join him. [This was the morass in front of Lord Stirling’s later position on Perrine Hill.]19

After being ordered to retreat from in front of Monmouth Courthouse, the artillery under Colonel Oswald "formed upon ... [an] eminence, which I suppose was about a quarter of a mile in the rear of where I was, [where] I discovered on my left General Maxwell's brigade and General Scott's detachment coming out of the wood upon this eminence I had formed for action, and had taken two pieces from General Scott's detachment and two from General Maxwell's brigade, making in all ten. I heard some person behind me ask one of my officers what we were doing there with the pieces, and why we did not retreat. I turned my horse about and saw it was General Maxwell. I told him I had my orders; upon which he said, very well, and went off ..." On being questioned later as to whether he was "certain that it was General Scott's detachment and General Maxwell's brigade that you saw come out of the wood, or their artillery only?" Oswald answered that he was "not certain that it was General Scott's detachment, but I got their artillery, and there was a body of men with the two pieces; but I am certain it was General Maxwell's brigade." Colonel Oswald remained on the hill for a short time and then retreated again at General Lee's order. "Just after I ascended the hill on the plain [after crossing the defile near Carr's house], Major Shaw [possibly John Shaw, 2nd Continental Artillery] came up, and said it was General Knox's order that I should form my pieces there; but before this, I had ordered the two pieces I had taken from Scott's detachment, and the two that I had taken from General Maxwell's brigade, to join their brigade again ..." The artillery did stellar service during the withdrawal, Brigadier-General Henry Knox stating that “The field pieces were repeatedly unlimbered and fired on the enemy, who advanced in our front in a scattered manner.”20 [More info on the Artillery]

At the beginning of the retreat Colonel Matthias Ogden, 1st New Jersey, entertained a belief that the movement was merely to consolidate the troops for defense. "The brigade was still moving on from the Court‑house. I rode again to General Maxwell, and asked him where the brigade should form. He said he had no orders for forming them. By this time we had crossed the [Middle] morass that was between the enemy's encampment and ours the evening after the action, and came near the hedge‑row [east of the West Morass (Spotswood Middle Brook), fronting Perrine Hill]. At this time I saw no disposition for facing the enemy, but understood that General Maxwell had orders to move his brigade near to some cross‑road. I begged of General Maxwell to let me halt my regiment; he consented, and I drew them up on the left of the hedge‑row, in a piece of wood [Parsonage Farm north wood, just east of “Mr. Tennent’s Bridge”], expecting to have had an opportunity of covering our men retreating. After I had been there six or eight minutes, Major [Aaron] Ogden came to me; he asked me how he could be of the most service to me; I told him by reconnoitring the enemy and giving me notice. As long as my right flank was secure, on my left was a morass, I apprehended no danger from that quarter ... In a short time after this, there was a pretty smart firing of musquetry on the right, in my front, immediately on which, a number of our men that had been engaged, retreated towards me in a direct line from the enemy; immediately on which I saw the enemy had crossed the morass on my left, and was moving down on that quarter, on which I ordered a retreat.”21

* * * * * * * * * * * *

“They answered him

with three cheers ...”

Washington Recovers the Day

Alexander Hamilton described the mid-day situation and the commander in chief’s response:

Not a word of all this [i.e., Lee’s retreat] was officially communicated to the General [Washington]; as we approached the supposed place of action we heard some flying rumours of what had happened in consequence of which the General rode forward and found the troops retiring in the greatest disorder and the enemy pressing their rear. I never saw the general to so much advantage. His coolness and firmness were admirable. He instantly took measures for checking the enemy’s advance, and giving time for the army, which was very near, to form and make a proper disposition. He then rode back and had the troops formed on a very advantageous piece of ground; in which and in other transactions of the day General Greene & Lord Stirling rendered very essential service, and did themselves great honor.22

As General Washington advanced with his troops on the road between Englishtown and Freehold he met Colonel Hamilton, who “told him he had come from our advance corps, and … from the situation he had left our van and the enemy’s rear in, they would soon engage.” That notion was soon dispelled; according to Washington aide Colonel Tench Tilghman, “a countryman rode up … he said he heard our people were retreating, and that that man, pointing to a fifer, had told him so [aide Lt. Col. Richard Harrison said the ‘fifer … appeared to be a good deal frighted’]. General Washington not believing the thing to be true, ordered the fifer under the care of a light-horseman to prevent his spreading a report … [to] the troops who were advancing …” Moving on Washington met Grayson’s and Patton’s Additional Regiments whose troops were “very much fatigued, and had been ordered off to refresh themselves …” The commander in chief asked Captain Cleon Moore, Grayson’s Regiment, “to take his men into a wood near at hand, as they were exceedingly heated and fatigued, and to draw some rum for them, and to keep them from straggling.” Colonel Tilghman recounted that Washington then “asked the officer who led, if the whole advanced corps were retreating? He said he believed they were … [and] scarcely said these words when we saw the heads of several columns of our advanced corps beginning to appear.”23

When word of Lee's withdrawal reached the commander in chief his aide Colonel Harrison volunteered to go forward and "bring him a true account of the situation." After crossing "the bridge in front of the line that was afterwards formed on the heights" Harrison

proceeded down the line, determined to go to the rear of the retreating troops, and met with Colonel Ogden [1st New Jersey]. I asked him ... whether he could assign the cause, or give me any information why the troops retreated. He appeared to be exceedingly exasperated, and said, By God! they are flying from a shadow. I fell in immediately after with Captain Mercer, who is Aid‑de‑Camp to Major‑General Lee, and ... put the same question to him. Captain Mercer seemed, by the manner of his answer ... to be displeased; his answer was, if you will proceed you will see the cause; you will see several columns of foot and horse ... The next field‑officer I met was Lieutenant‑Colonel [David] Rhea, of [the 2nd] New Jersey, who appeared to be conducting a regiment. I asked him uniformly the same question ... and he appeared to be very much agitated, expressed his disapprobation of the retreat, and seemed to be equally concerned (or perhaps more) that he had no place assigned to go where the troops were to halt. About this time I met with General Maxwell ... He appeared to be as much at a loss as Lieutenant‑Colonel Rhea, or any other officer I had met with; and intimated that he had received no orders upon the occasion, and was totally in the dark what line of conduct to pursue. I think nearly opposite to the point of wood where the first stand was made, I saw General Lee.24

Washington aide Lt. Col. John Fitzgerald rode forward with Harrison: "... About this time General Lee rode back towards that defile, with some scattering troops; I then advanced through a grain field, where [Lieutenant] Colonel Dehart [1st New Jersey] was taking a view of the enemy, and remained there until we thought it imprudent to stay any longer, as the British light‑horse began to come pretty near."25 Battlefield map

After Fitzgerald and Harrison moved forward, Washington and the remainder of his staff proceeded to follow. Colonel Tilghman recalled that after meeting some retreating soldiers,

we saw the heads of several columns of our advanced corps beginning to appear. The first officers the General [Washington] met were Colonel Shreve and Lieutenant‑Colonel Rhea, at the head of Colonel Shreve's [2nd Jersey] regiment. The General was exceedingly alarmed, finding the advance corps falling back upon the main body, without the least notice given to him, and asked Colonel Shreve the meaning of the retreat; Colonel Shreve answered in a very significant manner, smiling, that he did not know, but that he had retreated by order, he did not say by whose order. Lieutenant‑Colonel Rhea told me that he had been on that plantation, knew the ground exceedingly well, and that it was good ground, and that, should General Washington want him, he should be glad to serve him. General Washington desired Colonel Shreve to march his men over the morass, halt them on the hill, and refresh them. Major [Richard] Howell was in the rear of the [2nd Jersey] regiment; he expressed himself with great warmth at the troops coming off, and said he had never seen the like. At the head of the next column General Lee was himself …26 [See 1780 secret mission for more on Major Richard Howell]

Many years after the war 1st New Jersey Private John Ackerman recalled this withdrawal clearly in his pension deposition, stating "that his regement on that day was ordered by the Colo to retreat which was effected by passing through a morass in which he lost his shoes ‑ After retreating through this morass, his regement came to the road just as the troops under the immediate command of Gen Washington were passing ‑ Gen Washington halted his troops [the commander in chief and staff had actually ridden ahead of the main body of the army], and the retreating Regement was immediately paraded having become disordered in retreating through[h] the [morass] He well recollects that Gen Washington on that occasion asked the troops if they could fight and that they answered him with three cheers ..."27 [More NJ Soldier accounts.]

Lt. Col. Brooks witnessed the meeting of the two generals:

After having gone through the line [of defense at the hedge-row], I observed General Washington rising the height, and General Lee riding to meet him. Just as they had met I came up with General Lee. General Washington asked him what the meaning of all this was: General Lee answered, the contradictory intelligence, and his orders not being obeyed … His Excellency shewing considerable warmth, and said, he was very sorry that General Lee undertook the command unless he meant to fight the enemy, (or words to that effect). General Lee observed that it was his private opinion that it was not for the interest of the army, or America, I can’t say which, to have a general action brought on, but notwithstanding was willing to obey his orders … but in the situation he had been, he thought it by no means warrantable to bring on an action, or words to that effect … [Washington left for some time, and upon returning] asked General Lee if he would command on that ground or not; if he would, he [General Washington] would return to the main body, and have them formed upon the next height. General Lee replied, that it was equal with him where he commanded. Upon this General Washington rode off the field; General Lee rode to the right.28

General George Washington confronts Major-General Charles Lee at midday near the West Morass. An excellent rendering of soldier’s clothing at the time, with a variety of hats and coats seen, along with a mix of overalls and breeches. The troops formed on the right have left their coats and knapsacks behind at Englishtown because of the hot weather. The only discrepancy is the pullover hunting shirt pictured; only open-front hunting shirts have been documented. H. Charles McBarron, “Monmouth 28 June 1778” Soldiers of the American Revolution print series.

What actually passed between the two commanders during their initial meeting became the subject of much speculation. One account is patently false, another is doubtful. General Charles Scott, a profane man himself, replied to an interviewer in the early 19th century who wished to know if General Washington ever swore, “Yes, once. It was at Monmouth … he swore on that day till the leaves shook on the trees, charming, delightful … he swore like an angel from Heaven.” The Marquis de Lafayette remembered, also long after the fact, Washington calling Lee “a damned poltroon.” Historian Christopher Ward noted that both Scott’s colorful story and Lafayette’s remark are highly suspect, and, besides the fact that Scott was on another part of the field at the time the two generals met, entirely at odds with the commander in chief’s character. Other narratives are more believable. Private James Jordan, 2nd New Jersey, recalled of the incident, while retiring “we were met by Gen. Washington who came up with the Main Army riding a White Horse this petitioner was within a yard of him and heard him address Gen. Lee by asking him ‘What is this you have been about to day?’" Dr. James McHenry later testified, “While General Washington was forming the regiments under Colonel Stewart and Lieutenant-Colonel Ramsay, General Lee came up. General Washington, upon his approaching, desired of General Lee the cause of the retreat of the troops? General Lee hesitatingly replied, Sir. Sir. General Washington then repeated, I think, the question a second time; I did not clearly understand General Lee’s reply to him, but can remember the words confusion, contradictory information, and some other words of the same import. The manner … in which they were delivered, I remember pretty well; it was confused, and General Lee seemed under an embarrassment in giving the answer.” Aide Tench Tilghman supported the doctor’s version, adding that “Washington rode up to [Lee], with some degree of astonishment …” One source claims Lieutenant Thomas Marshall of Grayson’s Regiment later stated that Lee answered, “Sir, these troops are not able to meet British Grenadiers,” to which Washington replied, “Sir, they are able, and by God, they shall do it!” After serving at the hedge-row defense, Charles Lee was sent back to Englishtown, where several people remarked on seeing him later in the day.29

* * * * * * * * * * * *

“The Action was Exceedingly

warm and well Maintained …”

Infantry Fighting at the Point of Woods,

Hedge-row, and Parsonage

Gentleman volunteer Bernardus Swartout, serving with Cilley’s battalion of Scott’s detachment, wrote of Lee’s retreat, “we retired in great haste but in good order - the enemy pressed hard on our rear. After retreating two miles was met by Gen. Washington who was amazed to find us retreating - he ordered us to halt, form on a hill immediately in our front and face the enemy, accordingly did so, with alacrity, on a good piece of ground - the enemy had been advancing on us very fast, cutting our rear to pieces.”30 Battlefield map

Lt. Col. Tilghman noted that after encountering General Lee, “General Washington had not rode many yards forwards … when he met Lieutenant‑Colonel Harrison, his secretary, who told him that the British army were within fifteen minutes march of that place ... The General seemed entirely at a loss, as he was on a piece of ground entirely strange to him; I told him what Lieutenant‑Colonel Rhea [2nd New Jersey Regiment] had told me of his knowing the ground; he desired me to go and bring him as quick as possible to him; to desire Colonel Shreve to form his regiment on the hill, which was afterwards our main position, and I think, to get the two small regiments of Grayson's and Patton's there also, that the line might be formed as quick as possible. I conducted Lieutenant‑Colonel Rhea back to the General; when I got there, I saw Colonel [Henry] Livingston beginning to form his regiment along the hedge‑row, where the principal scene of action was that day ..."31

Following Washington’s meeting with Lee several fiercely contested infantry actions ensued on the American right involving some of Lee’s picked units. New Jersey Major Aaron Ogden told of his rear-guard position while Captain John Mercer set the stage for the first action at the Point of Woods, on the West Rhea plantation. Ogden testified, "After the remainder of General Maxwell's brigade had crossed the bridge [in front of Perrine Hill] … I went to let General Lee know that Colonel Ogden's [1st New Jersey] regiment was posted in a point of woods [Parsonage Farm] adjacent to the road which led to the bridge [over the West Morass], and that he intended to give the enemy a warm reception there." (Ogden was later forced to retire by a troops threatening his left.) Lee’s aide Captain Mercer stated the retreating troops made their way back to "the height occupied afterwards by Lord Stirling ... [on the other side of] the bridge where we first crossed ..." General Lee retained command of these troops after the commander in chief’s arrival, testifying later, “the instant General Washington came up and had issued a single order, I consider'd myself in fact reduc'd to a private capacity ... When he permitted me to reassume the command on the hill we were then on [across the morass fronting Perrine Hill], he gave me directions to defend it, in order to give him time to make a disposition of his army ...” Just east of the hedge-row General Anthony Wayne's troops went into the Rhea Plantation woods. Mercer then told Wayne "that General Lee's orders were, that he should defend that post ... and [after a short discussion] the action immediately commenced in that wood; General Lee then sent me into the rear to Colonel Ogden's regiment ... I saw there the Commanding Officer, who I did not know, and told him that General Lee's orders were, that he should defend that [Parsonage Farm] wood to the last extremity, and cover the retreat of the whole at the bridge; he replied, that the enemy had got upon his left, and they were very good men, and it would never do to have them sacrificed there. I mentioned to him, as I rode off, that they were not in more danger than those in front." Wayne’s fight in Rhea Plantation Woods, east of the hedge-row, was the first serious infantry action of the day, involving Stewart’s and Ramsey’s battalions, with a contingent of Virginians, against the Brigade of Guards. Shortly after Captain Mercer returned to General Lee, British troops forced Wayne’s regiments to retreat.32

Anthony Wayne described the Point of Woods (West Rhea Plantation) fight to his wife, “the Enemy following in force … Rendered it very Difficult for the small force I had to gain the main body, being often hard pushed and frequently Surrounded - after falling back about a mile we met His Excellency, who Surprised at our Retreat, knowing that Officers as well as men were in high Spirits and wished for Nothing more than to be faced about and meet the British fire - he Accordingly Ordered me to keep post where he met us with Stewarts & [Ramsey’s] Regiments and a Virginia Regt [the consolidated 4th/8th/12th Virginia] then under my Command with two pieces of Artillery and to keep [the Enemy] in play until he had an [opportunity] of forming the Remainder of the Army and Restoring Order - We had but just taken post when the Enemy began their attack with Horse, foot, & Artillery, the fire of their whole united force Obliged us after a Severe Conflict to give way …”33

To the rear of the Rhea Plantation woods was a hedge-row (also called a hedge-fence or fence), where the next combat occurred. General Lee recalled, “I understood General Wayne took the command in the point of the wood on our left, where Colonel Stewart had been halted … On their right on the opposite side of the plain, I had ordered Colonel Oswald, with four pieces of artillery …” Being in an exposed position in front of the line, “I ordered [the artillery] into the rear of Livingston’s … which regiment, together with Varnum’s brigade [and supported by a party of militia light-horse] … lined the fence [hedge-row] that stretch’d across the open field ... I sent Captain Mercer, my Aid‑de‑Camp, to Colonel Ogden, who ... had drawn up in the wood nearest the bridge in our rear, and ordered him to defend that post, to cover the retreat of the whole over the bridge. … These battalions having sustain’d with gallantry, and return’d with vigour, a very considerable fire, were at length successively forced over the bridge" to General Washington’s position on Perrine Hill.34

Colonel Laurens recalled the maddening withdrawal and the Continental troops’ first stand, “All this disgraceful retreating, passed without the firing of a musket, over ground which might have been disputed inch by inch. We passed a defile and arrived at an eminence beyond, which was defended on one side by an impenetrable fen, on the other by thick woods where our men would have fought to advantage. Here, fortunately for the honour of the army, and the welfare of America, Genl Washington met the troops retreating in disorder … [and] ordered some pieces of artillery to be brought up to defend the pass, and some troops to form and defend the pieces.” These were Captain David Cook’s and Captain Thomas Seward’s 3rd Continental Artillery batteries of two cannon each. Lt. Col. Oswald, 2nd Continental Artillery, asked later the whereabouts of Livingston’s Battalion “supposed he had gone into the woods on my left, where Colonel Stewart and Lieutenant-Colonel Ramsay were; but I afterwards understood he was at the hedge-row, where General Varnum’s brigade was.” Oswald then described the hedge-row fight, “I brought up the rear with Captain Cooke’s two pieces, and placed them on an eminence, just in rear of the hedge-row, where I found the troops formed. Through the breeches that had been made in the fence I discharged several grapes of shot at the enemy, the infantry being engaged with them.” Captain-Lieutenant John Cumpston, 3rd Continental Artillery, served with Cook at the hedge-row. Cumpston related that, after stopping during the retreat to fire at the British, “we then limbered our pieces and retired a short distance, formed in the rear of a party of troops that were to cover our pieces. The enemy were then advancing; a very heavy fire began of musquetry in our front and left wing. General Knox gave us … orders to give the enemy a shot. I believe our people made a stand there about two minutes; after giving them two or three charges of grape shot, we were ordered to retire … across the morass. By the time we crossed it with our pieces, there began a cannonade from our army who were on the hill.”35

Laurens also recalled the hedge-row action:

The artillery was too distant to be brought up readily, so that there was little opposition given here. A few shot though, and a little skirmishing in the wood checked the enemy’s career ... We were obliged to retire to a position, which, though hastily reconnoitred, proved an excellent one. Two regiments were formed behind a [hedge] fence in front of the position. The enemy’s horse advanced in full charge with admirable bravery to the distance of forty paces, when a general discharge from these regiments did great execution among them, and made them fly with the greatest precipitation. The grenadiers succeeded to the attack. At this time my horse was killed under me. In this spot the action was the hottest, and there was considerable slaughter of the British grenadiers. [Colonel Henry Monckton, commander 2nd Grenadier Battalion, was killed in this action.] The General ordered Woodford’s brigade [of Major-General Greene’s wing] with some artillery to take possession of an eminence [Comb’s Hill] on the enemy’s left and cannonade from thence. This produced an excellent effect. The enemy were prevented from advancing on us, and confined themselves to cannonade with a show of turning our left flank. Our artillery answered theirs with the greatest vigour. The General seeing that our left flank was secure, as the ground was open and commanded by it, so that the enemy could not attempt to turn it without exposing their own flank to a heavy fire from our artillery … In the meantime, Genl Lee continued retreating. Baron Steuben was order’d to form the broken troops in the rear.36

Several British officers described the fighting at Rhea Woods and the hedge-row, the preceding march, and ensuing cannonade. Lieutenant William Hale, 2nd Grenadier Battalion, related his experience, beginning with the pursuit of Lee’s retreating troops to the morass fronting Perrine Hill.

… such a march I may never again experience. We proceeded five miles in a road composed of nothing but sand which scorched through our shoes with intolerable heat; the sun beating on our heads with a force scarcely to be conceived in Europe, and not a drop of water to assuage our parching thirst; a number of soldiers were unable to support the fatigue, and died on the spot … and the whole road, strewed with miserable wretches wishing for death, exhibited the most shocking scene I ever saw. At length we came within reach of the enemy who cannonaded us very briskly without doing much damage, and afterwards marching through a cornfield saw them drawn up behind a morass on a hill with a rail fence in front and a thick wood on their left filled with their light chosen troops. We rose on a small hill commanded by that on which they were posted in excellent order notwithstanding a heavy fire of Grape[shot], when judge of my inexpressible surprise, General Clinton himself appeared at the head of our left wing accompanied by Lord Cornwallis, and crying out 'Charge, Grenadiers, never heed forming'; we rushed on amidst the heaviest fire I have yet felt. It was no longer a contest for bringing up our respective companies in the best order, but all officers as well as soldiers strove who could be foremost, to my shame I speak it. I had the fortune to find myself after crossing the swamp with three officers only, in the midst of a large body of Rebels who had been driven out of the wood by the 1st Battalion of Grenadiers, accompanied by not more than a dozen men who had been able to keep up with us; luckily the Rebels were too intent on their own safety to regard our destruction. Lt. [Joseph or William] Bunbury [49th Regiment] killed one of them with his sword, as we all might have done, but seeing a battalion running away with their Colours, I pushed for them with the few fellows I had, but to my unutterable disppointment they out ran us in a second. Col. Monckton was shot through the heart at the first charge, to the unspeakable loss of the Regt. … his body which could not be found in the spot where he fell by a party I sent to bury it, was intered by the Rebels the next day with military honours. Lt. Kennedy of the 44th Grenadiers … was killed by the same fire. The Column which we routed in this disorderly manner consisted of 4000, the force on our side not more than 800, during the whole our left flank was left entirely exposed and commanded by the hills of which they afterwards availed themselves. In the mean time the pursuit of this column brought us on their main Army led by Washington, said by deserters to be 16,000. With some difficulty we were brought under the hill we had gained, and the most terrible cannonade L[or]d. W. Erskine says he ever heard ensued and lasted for above two hours, at the distance of 600 yards; on our side two medium twelves, as many howitzers and 6 six-pounders which were answered by fourteen pieces, long twelves and french nines; our shells [i.e., howitzers] and twelves, which were admirably conducted by a Capt. Williams, did most horrible execution among their line drawn up on the hill. The shattered remains of our Battalion being under cover of our hill suffered little, but from thirst and heat of which several died, except some who preferred the shade of some trees in the direct range of shot to the more horrid tortures of thirst. Capt. Powell of the 52nd Grenadiers, one of these [seeking shade] had his arm shattered to pieces … At length finding we did not take possession of the hills [Combs Hill] on their right, they brought some cannon on them and obliged us to move through the wood to a hill at a greater distance, and some [British] brigades coming up both kept possession of their field from which they moved that evening, and we in the night. Our battalion lost 98, 11 officers killed and wounded, Major Gardner shot very badly through the foot …37

Captain John Peebles, Grenadier Company, 42nd Regiment, noted that “about 2 miles to the westwd. Of the Village the Gr[enadie]rs. attack’d, & the Light Infy. Were sent to the righ[t] The 1st. Battn. Light Infantry & Queen Rangers were dispatch’d to the right to try to gain the Enemy’s left flank, but meeting swamps & much impediment in the Woods they did not get up in time, mean while the Brigade of Guards & two Battalions of British Grenrs. After a very quick march moved up briskly & attack’d the Enemy in front receiving a heavy fire as they approach’d of both cannon and musketry & when within a short distance they pour’d in their fire & dashing forwards drove the enemy before them for a considerable time, killing many with their Bayonets but seeing a fresh line of the Enemy strongly posted on t’other side [of] a Ravine & Swamp & well supplyed with Cannon & having suffer’d much both from the fire of the Enemy & fatigue & heat of the day, they were order’d to retire till more Troops came up to their Support …”38

The 13 July New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury contained an interesting, though unattributed, British account of the combat, again beginning with the confrontation at Freehold:

The Action commenced at Twelve, on the hottest Day imaginable. After a March of eight Hours, the British Guards forming the Rear of the Army, the Rebels insulting the flanking Parties, at Eleven the General reconnoitered the Enemy, and finding them in Force, ordered an Halt on the Heights of Freehold … The Rebel Battalions shewing themselves with a Disposition to stand; the Commander in Chief ordered the Rear of the Army to form in the Front, and the Light Horse to advance, and Charge those in the Front of the Wood leading to Freehold Court-House, at the same Time commanding the first Battalion of Guards to support the Cavalry, and follow the Charge with Bayonets, while the Cavalry were advancing during the Moment in which the Guards were Loading, in Consequence of Orders, they received a Fire on the Right from the Wood [West Rhea Plantation], of 300 of the Enemy posted in Ambush. Orders were now given to face to the Right, and Charge through the Wood. This Order was executed with such Alacrity; that the Rebels were forced with Bayonets through a deep Morass, a Wood hardly penetrable, during a very hot Fire, cross a Plain and Ravine, to the Edge of a second Wood; when the Ardour of the Troops was most judiciously stopped by Orders from the General, who perceiving them affected by the excessive Heat … this Influence having occasioned a Check to the first Line of the Rebel Army, they retreated under the Cover of a Cannonade, which occasioned the Loss of the gallant Lieut. Col. Monckton, and several other very respectable Officers.39

Lt. Hale, 2nd Battalion Grenadiers, gave further details in a 14 July letter from New York: “I escaped unhurt in the very hot action of the 28th last month, allowed to be the severest that has happened, the Rebel’s Cannon playing Grape and Case upon us at the distance of 40 yards and the small arms within little more than half that space; followed by a most incessant and terrible cannonade of near three hours continuance; you may judge from the circumstances of our battalion guns, 6 pounders, firing 160 rounds, and then desisting only lest ammunition should be wanting for Case shot; of the roar kept up by our twelves [12 pounder cannon] and howitzers, answered by near twenty pieces from their side on a hill 600 paces from ours … Our Comp[any]. which I commanded lost 3 killed and one wounded, supposed mortally …”40

Lt. Col. Laurens noted that following the hedge-row action “The cannonade was incessant and the General ordered parties to advance from time to time and engage the grenadiers and guards.” Two of these advances, both post-bombardment, resulted in serious actions. One was Cilley’s attack on the 42nd Regiment at the Sutfin Farm (described in the next section). The other was the fight at the Parsonage, to which Anthony Wayne alluded in a July letter, “a Most tremendous Cannonade Commenced on both Sides, and Continued near four Hours without Ceasing - during this time every possible Exertion was made use of by His Excellency and the Other Generals to Spirit up the Troops and prepare them for an Other tryal - the Enemy began to Advance again in a heavy [Column], against which I ordered some [blank] & advanced with some of my [troops] to meet them - the Action was Exceedingly warm and well Maintained on each Side for a Considerable time … Every General & other officer (one excepted) did Everything that could be expected on this Great Occasion, but Penns[ylvani]a shewed the Road to Victory …”41

First Lieutenant Alexander Dow, Malcolm's Additional Regiment, described the Parsonage fight in a May 1781 letter to Congress:

I was … at Munmoth Battel in a sharp Incanter ageanst British Graniders Whilst Lt Coll [Rudolph] Bunner [3rd Pennsylvania Regiment, killed 28 June 1778] fell near me [and] Coll [Francis] Barber [3rd New Jersey Regiment] much wounded / four subalterns of our Regt [were] wounded one of which [was] Adjintant Talman [Peter Taulman, Malcolm's Regiment, shot in the throat] Closs by my side / I Commanded the platun on the left of our partey and being Closs prest by the right of the Enemy in frunt Lost three of my men the English Comanding Officer on the right of the Enemy holoring Com on my brave boyes for the honour of Great briton, I ordred my men to Lavel at him and the Cluster of men near him as I dreaded the next momant he would ride me down / he droped [and] his men slackened ther pase whin Coll [Oliver] Spencer [Spencer’s Additional Regiment] ordred me to fall back the rest of ours wer in flight / so sune as we gave way Lo[r]d Starlings [American Major General William Alexander, Lord Stirling] Artillery Played on the Enemy so well That they Run Back and we Imeditly rallied and returned to our own Ground wher we remained under arms till next morning / I sune found that the Officer who fell By my Directions provd to be Coll [Henry] Munkton [commander 2nd Grenadier Battalion]42

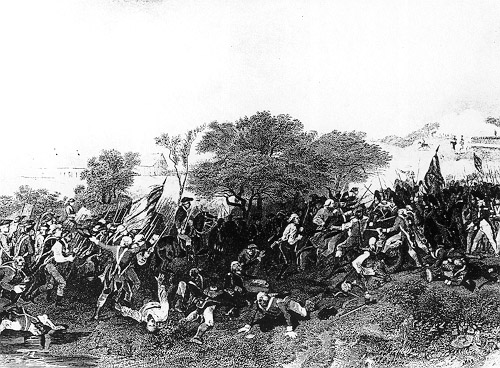

Alonzo Chappel’s 19th century rendering of the Monmouth battle, based on the late-day Parsonage Farm fight. Alonzo Chappel, "Battle of Monmouth" (Johnson Fry & Co., New York, 1868).

As with many first-hand battle accounts some details are not quite correct. In this case the inaccuracy concerns Lieutenant Dow’s claim to have been responsible for Colonel Monckton’s death. Historian Garry Stone places Dow’s Monmouth narrative in its proper context:

The Parsonage fight was between three small regiments commanded by Brigadier-General Anthony Wayne and the 1st Battalion of British Grenadiers. The 3rd Pennsylvania Regiment was on the Continental right, and as implied by Dow, Malcolm’s and Spencer’s Additional Regiments were to the left. Malcolm’s Regiment may have been on the extreme left, at the Parsonage barn and dwelling, as an account of Adjutant Peter Taulman’s wounding states that he “crawled behind the barn.” As none of the battalion officers of the 1st Grenadiers was killed or wounded apparently Dow’s men killed only an officer’s horse. Lieutenant-Colonel Monckton, commander, 2nd Battalion of British Grenadiers, had been killed hours earlier during the Grenadiers’ attempt to cross the bridge between the Parsonage Farm and the Continental positions on the Perrine Farm.43

Lt. Col. Laurens will have the last word on these actions, “The [British] horse shewed themselves no more. The grenadiers shewed their backs and retreated every where with precipitation. They returned, however again to the charge, and were again repulsed. … Several officers are our prisoners. Among their killed are Col Moncton, a captain of the guards, and several captains of grenadiers … B. Genl Wayne, Col. Barber, Col. Stewart, Col. Livingston, Col. Oswald of the artillery, Capt [Samuel] Doughty [2nd Continental Artillery] deserve well of their country, and distinguished themselves nobly.”44

* * * * * * * * * * * *

"The

finest musick, I Ever heared."

Afternoon Battle Artillery Duel, and Cilley’s Attack on the 42nd Regiment

[Information on Artillery and American order of battle]

Lt. Col. Dearborn, Scott’s detachment, did not testify at Major General Lee’s court martial in July and August 1778, but his journal entry gives a clear, concise view of events as he saw them up to this point:

28th haveing Intiligence this morning before sun Rise that the Enimy ware moving, we ware Ordered, together with the Troops Commanded by the Marquis & Genrl. Lee (in the whole about 5000) to march towards the Enimy … at Eleven o Clock A.M. after marching 6 or 7 miles we arriv’d on the Plains Near Monmouth Court House, Where a Collumn of the Enimy appeared in sight. A brisk Cannonade Commens’d on both sides. The Collumn which was advancing towards us Halted & soon Retired, but from some moovements of theirs we ware Convince’d they Intended to fight us, shifted our ground, form.d on very good ground & waited to see if they intended to Come on. We soon Discovere’d a Large Collumn Turning our Right & an Other Comeing up in our Front With Cavelry in front of both Collumns Genrl. Lee was on the Right of our Line who Left the ground & made Tracks Quick Step towards English Town. Genrl. Scots Detatchment Remaind on the ground we form.d on until we found we ware very near surrounded- & ware Obliged to Retire which we Did in good order altho we ware hard Prest on our Left flank.- the Enimy haveing got a mile in Rear of us before we began to Retire & ware bearing Down on our Left as we went off & we Confin’d by a Morass on our Right. after Retireing about 2 miles we met his Excelency Genrl. Washington who after seeing what Disorder Genrl. Lee.s Troops ware in appeer’d to be at a Loss whether we should be able to make a stand or not. however he order’d us to form on a Heighth [Perrine Hill], & Indevour to Check the Enimy …45

Cilley’s and Parker’s battalions of Scott’s detachment formed on the hill, along a fence marking the Perrine/Sutfin farm property lines; most of the remainder of Lee’s troops continued retreating. The Jersey Brigade reached Perrine Hill before Scott’s troops. Private David Cooper, a levy serving nine months with the 1st New Jersey, recalled in his 19th century pension deposition, “On the morning of the Battle we were marched within a Mile of Monmouth [and] there changed our direction & Marched to the ground where the battle was fought / we [the 1st and 2nd Jersey regiments] were placed on the extreme Left & in the rear of the first lines where we remained during the action …" [Additional NJ accounts: Officers; Soldiers]. In that position the two Jersey regiments were out of musket range, but suffered some casualties from artillery (General Maxwell with the 3rd and 4th regiments had been sent back to Englishtown). Sergeant Ebenezer Wild, whose 1st Massachusetts Regiment belonged to Glover’s Brigade, Lord Stirling’s Left Wing, wrote of the cannonade, “About 2 o’clk … Our Division formed a line on the eminence about a half a mile in the front of the enemy, and our artillery in our front. A very smart cannonading ensued from both sides. We stayed here till several of our officers & men were killed and wounded. Seeing that it was of no service to stand here, we went back a little ways into the woods; but the cannonading still continued very smart on bout sides about two hours …”46 Henry Dearborn also noted the danger,

we form.d & about 12 Peices of Artillery being brought on the hill with us: the Enimy at the same time advancing very Rappedly finding we had form.d, they form.d in our front on a Ridge & brought up their Artillery within about 60 Rods [330 yards] of our front. When the briske[s]t Cannonade Commenced on both sides that I Ever heard. Both Armies ware on Clear Ground & if any thing Can be Call.d Musical where there is so much Danger, I think that was the finest musick, I Ever heared. however the agreeableness of the musick was very often Lessen’d by the balls Coming too near - Our men being very much beat out with Fateague & heat which was very intence, we order.d them to sit Down & Rest them Selves …47

Georgian Dr. William Read was traveling to join Washington’s army that June, and left a compelling account of the cannonade and its aftermath (Read wrote his narrative in the third person):