A SCORE SETTLED; A BROWN BESS TROPHY TAKEN

Bob McDonald

"We left our winter cantonments, crossed the Schuylkill and encamped on the left side of that river, just opposite to our winter quarters. We had lain here but a few days when we heard that the British army had left Philadelphia and were proceeding to New York, through the Jerseys. We marched immediately in pursuit."

Thus Private Joseph Plumb Martin of the 8th Connecticut Regiment described the rapid departure of the Continental Army from Valley Forge in mid-June, 1778. After six months in the squalid “log hut city”, during which rampant disease and chronic breakdowns of commissary supply had created the risk of literal disbandment, the Continentals marching from Valley Forge were now a “new-modeled” army, far more formidable than the one that had come to those wooded ridges the prior December. Aptly named, the camp and the events which took place there had indeed forged an American army the men of which would be appropriately described as having “constitutions like iron.”

Unprovided with nearly everything on the bleak hills above the Schuylkill, the result had not been the army’s dispersing through the massive desertions or contagious mutinies that General Washington considered distinct possibilities; it had been the opposite. Deprivation and the perception of virtual abandonment by Congress and their countrymen had created among the Continentals a degree of determination and esprit de corps that they had never previously achieved. Having been all but marooned by both the loosely-confederated national government and their respective home states, the regionally disparate segments of the army pulled closer together. The prior strong biases and open animosities, which in the war’s initial years had pitted New England “yankees” against “southerners” from west of the Delaware, became the dross of the Valley Forge winter. Thereafter, the Continentals would be one army, their strongest ties and deepest commitments being to their commander and to each other.

A second key factor facilitating the new-model army had been the arrival in camp of Baron von Steuben and his subsequent appointment as inspector general. During the three years prior to that spring, the Continentals had received training in maneuvers and field “evolutions” that had been at the discretion of individual regimental colonels, were usually taught by non-com’s, and that, resultantly, varied widely between units, both as to technique and effectiveness. The typical end-result performance, unsurprisingly, rarely rose above mediocre. Through intense effort and in record time, Steuben creatively blended and simplified European tactics to mesh with the pragmatic individualism of the Continentals. Placing responsibility squarely on regimental officers, he began to guide the previously non-coordinated cogs toward becoming a smoothly operating machine, an American army that, finally, might be equal to the challenge of a major stand-up slug fest with British regulars and their German allies.

That latter goal was the third and perhaps deepest source of fuel for the “new” Continental Army that marched, as Private Martin phrased it, “immediately in pursuit” of the enemy then evacuating Philadelphia. It had a major score to settle. For sixteen months prior to its arrival at Valley Forge, Washington’s main army had been, with very few exceptions, consistently and humiliatingly bested. Flanked and nearly trapped on Long Island in August of 1776, the Americans had then been again surprised at Kip’s Bay and forced entirely from Manhattan. The subsequent disappointing results at White Plains and the disastrous loss of Fort Washington had next sent the Continentals reeling in retreat entirely through New Jersey and across the Delaware River. The ensuing ten-day miracle campaign of Trenton and Princeton, while certainly a critically essential strategic and political coup buoyant of the cause during its darkest hour, had been two adroit hit-and-run raids, neither being a major stand-up engagement. Eight months later another British flank march had left the Continentals feisty but very clearly outperformed at Brandywine. Thereafter, in quick succession, Anthony Wayne’s Pennsylvanians had been surprised and many put to the bayonet at Paoli, several feints and a stolen march had yielded to the enemy the capital city of Philadelphia, and Washington’s conceptually viable but dangerously intricate attack plan of early October 1777 at Germantown had ended in frustrated effort and a twenty-mile withdrawal.

It was minimally if at all surprising, then, that many a British officer continued to regard the “rebel” army as ragamuffins and “country clowns.” Aware of both their to-date track record and their enemies’ opinion of them, the new-modeled Continentals now marched from Valley Forge with an intense desire for redemption. For some among them, there was the additional goal of personal vengeance. In the same company of the 8th Connecticut with Private Joseph Plumb Martin marched another New England teenager, Private Jonathan Preston. To him, there was an even greater score to settle.

As was typical of the times, nineteen-year-old Preston came from a large family, having three brothers, five sisters, and two step-brothers born of his widowed father’s remarriage. Among the four Preston boys old enough to enlist, three had joined. The eldest, Hackaliah, had been the first to commit, signing up with the 2nd Battalion of Connecticut State Troops in June, 1776. Twenty-four-year-old Amasa had enlisted in the 8th Connecticut Regiment, Continental Line in March, 1777. Setting out from the family homestead in Winchester, Jonathan also joined the 8th and united with his brother at Peekskill, New York in August. By that time, however, Amasa may have been the eldest surviving of the three brothers in arms.

Hackaliah’s unit had been among two full brigades raised by Connecticut the prior summer in response to General Washington’s anticipation that the focus of the British would fall upon New York following their being forced to evacuate Boston. The 2nd Connecticut Battalion had been among those American troops that withstood the attacks on the Brooklyn Heights in August of 1776, and were saved from disaster by Washington’s remarkably successful withdrawal across the East River. On September 15, however, the British military hammer had dropped again with shocking effect. An amphibious landing at Kip’s Bay had provided the key to an invasion that cost the Americans the city of New York.

It had also cost the Preston's a brother, Hackaliah’s unit being posted along the lines just south of Kip’s Bay. The patriot defense was crushed with humiliating speed, the 2nd Connecticut Battalion alone losing more than twenty officers and men simply “missing” in the massive confusion. Some were reported by surviving comrades to have been slain on the spot by bayonet-wielding Hessian troops. For most, however, there would be months or even years aboard the infamous British prison ships on the East River. Eventually, an estimated 11,000 unmarked American graves would line the Brooklyn shore, among them that of Hackaliah Preston.

Among the 4,000 troops led by Major General Charles Cornwallis at the Kip’s Bay invasion that September 15 had been the 33rd Regiment of Foot. The 33rd, in fact, had been Cornwallis’ own regiment and he remained its ex-officio colonel. It was a model unit, the flower of His Majesty’s forces, described in a 1774 inspection report by Major General Howe as being “... exceedingly expert at their duties. The men are well dressed. Remarkably upright, strictly silent under Arms... The Battalion is exceedingly rapid in all movements.” In his summation, Howe described the 33rd as being “far superior to any other Corps within my observation.” Its battle record during the American Revolution, exceeded in number of engagements by only one other British regiment, would clearly reflect the extent to which it was regarded and relied upon. As the men of the 33rd departed the “rebel” capital and began their march across southern Jersey toward New York in mid-June 1778, they already were veterans of Brooklyn Heights, Kip’s Bay, Harlem Heights, White Plains, the captures of both Fort Washington and Fort Lee, Brandywine and Germantown.

As was the case with the large majority of His Majesty’s troops in America, the 33rd was armed with the newest and best that the Tower of London armory had to offer, the first-pattern Short Land musket, the so-called “second-model Brown Bess.” With its dark walnut stock, brightly burnished iron barrel and lock, and its gleaming brass furniture, this ten-pound .75 caliber musket and its bayonet with seventeen-inch blade had made the British regulars awesomely effective in close-range engagements and hand-to-hand combat. Like his comrades, one of the men now marching northeast through New Jersey carried such a musket engraved “33 REGt” atop the barrel. It also bore on the brass escutcheon plate the engraved identification markings uniquely associated with his having been issued this particular weapon, the so-called rack numbers. His read “L/51.”

"We passed through Princeton and encamped on the open fields for the night, the canopy of heaven for our tent. Early next morning we marched again and came up with the rear of the British army. We followed them several days, arriving upon their camping ground within an hour after their departure from it. We had ample opportunity to see the devastation they made in their rout; cattle killed and lying about the fields and pastures,... household furniture hacked and broken to pieces; wells filled up and mechanics’ and farmers’ tools destroyed... Such conduct did not give the Americans any more agreeable feelings toward them than they entertained before."

As recalled in his memoirs, Joseph Plumb Martin, Jonathan Preston and the rest of the 8th Connecticut Regiment were provided even more fuel for their drive toward revenge as the Continentals shadowed the left of Sir Henry Clinton’s extended column while it slowly moved into mid-state New Jersey. The depredations on such a large scale might have been an accepted part of warfare in Europe; in the two-year-old United States of America, they were not. Just as the King’s regulars had little respect for the “rebels” as an effective army, the Continentals returned the disdain through a perspective of the enemy as arrogant, pompous and, above all else, ruthless foreign invaders, the latter particularly directed toward the Hessians and other German “hireling mercenaries.” Seeing the widespread destruction among the Jersey civilian population simply compounded the Americans’ animus as they concentrated their forces and closed the distance toward the British column. Having marched northeast from Valley Forge to cross the Delaware on June 21 and 22, the main portion of Washington’s army had reached Hopewell, New Jersey the following day, but they were still twenty miles from the enemy force and Washington knew that if he was going to strike, it would need be soon. Having received intelligence reports of a large fleet being anchored off Sandy Hook, it was clear to him that Clinton’s intent was not to remain vulnerable by marching all the way to New York, but to return afloat via the protection of British naval superiority.

At a council-of war held at Hopewell on the morning of June 24, Washington called for the opinions of his subordinate commanders. Aside from the perspectives of the always-ready-for-a-brawl Anthony Wayne and those of Nathanael Greene and Lafayette, the predominant mood among the army’s command was to avoid risking a potentially adverse engagement and to allow Clinton to depart. Most strident in expressing his opinions against any significant interference with the enemy force was that personification of “bizarre”, the army’s second-in-command, Major General Charles Lee. In summarizing the advice offered by the council, Washington’s aide Alexander Hamilton commented that it would “... have done honor to the most honorable society of midwives, and to them only.” Unsurprisingly, the innately aggressive Washington rejected the majority opinion of allowing the British to return to New York unchallenged, later that day ordering a 1,500-man detachment to advance and dog the enemy column more actively. On the 25th, with the main body of the Continentals having reached Kingston, he upped the ante by expanding the advance force to about 2,500. His orders to Lafayette, in command of the forward thrust, could leave no doubt whatsoever that his intent was to drop the match into the keg:

"You are to use the most effectual means for gaining the enemy’s left flank and rear, and giving them every degree of annoyance... You will attack them as occasion may require by detachment, and, if a proper opening shd. be given, by operating against them with the whole force of your command."

Charles Lee, a career British officer before emigrating to America in 1773, continued to firmly grasp the opinion that Continental troops were still no match for His Majesty’s army, and his unequivocal opposition to an aggressive move against Clinton’s column had probably left little doubt in Washington’s mind that his second-in-command was not the most enthusiastic man to lead the advance detachment’s thrust, that assignment therefore going to Lafayette. Late on the 25th, now chagrined by the rapidly escalating commitment of troops to the forward element, Lee did a turnabout and asserted his being entitled to the post of honor. Likely more than a little surprised by Lee’s abrupt reversal, and probably at least somewhat concerned about the wisdom of doing so, Washington nonetheless adhered to propriety and granted Lee’s request the following morning. While the main body of the Continentals proceeded to Cranbury, the commander made another decision. Both to notch up the stakes even further and as a buffer to protect Lafayette’s morale and reputation in being superseded by Lee, Washington expanded the advance wing’s strength to more than 5,000. Now added to this forward thrust was the brigade of Brigadier General James Varnum, under the temporary command of Colonel John Durkee, a component unit of which was the 8th Connecticut Regiment. They were marching toward a small New Jersey village named, quite ironically, Englishtown.

Only five miles to the southeast, the long British column was centered on the town of Freehold, site of the Monmouth County courthouse. Within General Cornwallis’ rearguard division of Clinton’s 20,000-man army was the 33rd Regiment of Foot. The stage was now set between these two small New Jersey towns for what was about to erupt as the longest and perhaps most tenaciously fought engagement of the American Revolution.

The Score Settled

"We were early in the morning mustered out and ordered to leave all our baggage under the care of a guard... and to prepare for action. The officer who commanded the platoon I belonged to was a captain,... 'Now,' said he to us, 'you have been wishing for some days past to come up with the British, and you have been wanting to fight, -- now you shall have fighting enough before night.'”

Anticipating nothing from the Americans beyond minor harassment and sniping, Clinton had allowed his army more than an entire day of rest in the area of Freehold. Now, early on the morning of June 28, while Private Martin listened to his captain’s avowal and Jonathan Preston and the other men of the 8th Connecticut unslung and piled their knapsacks, the British column was again put in motion northeastward. Intelligence of the enemy’s resumption of its march was delivered to General Washington as rapidly as roving aides and New Jersey militia scouts could ride the few miles to his headquarters. In response, the commander-in-chief immediately sent a courier to General Lee with orders to advance toward Freehold and launch his attack “… unless there should be very powerful reasons to the contrary”, along with the assurance that the commander would be advancing to Lee’s support with the main body of the army. Very quickly, however, the deficiencies of Major General Charles Lee began to affect the developing engagement. Having done little or no reconnaissance during the prior evening, his understanding of the enemy position and the intervening ground was minimal. Additionally, he had communicated no plan of action, either specific or general, to his primary subordinates. Now, the receipt of conflicting information began to substantially confuse Lee. Shortly after receiving Washington’s intelligence that the enemy column was again in motion northeastward away from Freehold, Lee also was provided information from other nearby scouts that, apparently to the contrary, a British force was in formation and advancing to launch an attack on his own marching column. Concluding that these two interpretations were either/or alternatives, when in fact both were true, Lee slowed his advance to a virtual crawl.

Not until shortly before 9:00 AM did Lee muster the decisiveness to order an advance detachment of about 750 men to frontally assault the approaching enemy, while he personally would lead a flanking move toward its rear. Even now, though, Lee’s dissonance and indecision continued to build. The advance detachment had only begun its forward motion when it received follow-up orders from Lee that the movement was intended as only a feint and that a serious engagement should be avoided. While those involved attempted to discern the sense of these contradictions, a small mounted force of Americans noticed a sizable gap in the British column and immediately attacked it. Although soundly conceived and aggressively launched, this assault was basically foredoomed due to sheer weakness of numbers. The withdrawal of these horsemen, however, had a much greater effect on the entire advance operation. Seeing the retreat of this small American force, and the concurrent advance of a body of British horse to the front, some within Lee’s main body, including its commander, mistakenly interpreted it as the fleeing of the advance force’s initial thrust. By about 10:30 AM, the 8th Connecticut, part of Lee’s main force supposedly launching an encircling of the British left flank, found itself instead in a rapidly deteriorating situation:

"It was ten or eleven o’clock before we got through these woods and came into the open fields. The first cleared land we came to was an Indian cornfield, surrounded on the east, west and north sides by thick tall trees. The sun shining full upon the field, the soil of which was sandy, the mouth of a heated oven seemed to me to be but a trifle hotter than this ploughed field; it was almost impossible to breathe. We had to fall back again as soon as we could, into the woods. By the time we had got under the shade of the trees and had taken breath, of which we had been almost deprived, we received orders to retreat, as all the left wing of the army, that part under the command of General Lee, were retreating. Grating as this order was to our feelings, we were obliged to comply."

Unsurpassed by any other factor, the heat of June 28, 1778 would be literally unforgettable to the men who fought at Monmouth. By mid-morning the air temperature was already well above 90 degrees, but the oppressive humidity and the reflective sandy soil of New Jersey far compounded the misery. Nearly as hot as the surrounding fields, Private Martin’s “grating” anger was virtually universal throughout Lee’s advanced wing. To Lafayette, Wayne and many others, the withdrawal order was completely incomprehensible and was initially questioned as being a false rumor. Even this early in the engagement, there were the beginnings of thoughts of Lee’s true allegiance. But, for Charles Lee, the worst was yet to come.

As additional British forces were committed to capitalize on the unbelievable American retreat, the Continental withdrawal began to lose its cohesion and discipline. After the so strongly sought infusion of professionalism and esprit developed during the Valley Forge spring, the sight of a small number of American troops literally “on the run” shocked and infuriated the majority of their comrades. Not again! But, when Lee was able to arrest the flight and form a defensive position on advantageous ground, that line held only briefly, its infuriating commander again ordering a resumption of the unwarranted flight. As this flurry of stop-start orders and the confusion of shaken morale swirled in the scorching Jersey heat, more men became disheartened and the entire advance wing was soon moving in massed confusion back up the narrow clogged road to Englishtown and the main Continental force. With both sides of the road hemmed in closely by marshy wetland, and with increasing enemy musketry and artillery fire pounding from the rear, much of Lee’s force had now degenerated to a disorderly fleeing mob. It was a critical moment, and one that was custom made for the stuff of legend:

"We had not retreated far before we came to a defile, a muddy, sloughy brook. While the artillery were passing this place, we sat down by the roadside. In a few minutes the Commander in Chief and suite crossed the road just where we were sitting. I heard him ask our officers 'by whose order the troops were retreating,' and being answered, 'by General Lee’s,' he said something, but as he was moving forward all the time this was passing, he was too far off for me to hear it distinctly. Those that were nearer him said that his words were 'd—n him.' Whether he did thus express himself or not I do not know. It was certainly very unlike him, but he seemed at the instant to be in a great passion; his looks if not his words seemed to indicate as much. After passing us, he rode on to the plain field and took an observation of the advancing enemy. He remained there some time upon his old English charger, while the shot from the British artillery were rending up the earth all around him. After he had taken a view of the enemy, he returned and ordered the two Connecticut brigades to make a stand at a fence, in order to keep the enemy in check while the artillery and other troops crossed the before-mentioned defile."

Privates Martin, Preston and the rest of the 8th Connecticut Regiment were also just out of earshot of the celebrated first confrontation of Washington with his bumbling second-in-command. In spite of several memoirs written by purported witnesses long after the event, there is really no reliable contemporary evidence of what was assuredly a tense and heated exchange. What can be said with certainty, however, is that the commander maintained a lifelong campaign to keep his temper in check. On the very few occasions when he failed in that effort, the results were explosive, volcanic and unforgettable. At Kip’s Bay, the American line’s collapse and retreat had so infuriated Washington that he, as we would today say, completely “lost it”, slamming his cocked hat to the ground, striking at fleeing men with the flat of his sword, screaming invectives and whirling himself into complete emotional exhaustion. As the British forces closely approached, his staff needed to take his horse’s reins and lead him from the field. It is doubtful that his encounter with Lee at about noontime on this June day was nearly as eruptive, but the records suggest that he indeed did verbally accost Lee with scorching rage and, likely, with swearing. A concurrent characteristic of Washington’s few recorded outbursts of anger, however, was their brevity and his rapid recovery of control. In all likelihood, most of the thunderstruck “steam” had blown off before the two men met. In any event, after listening to Lee’s stammering excuses and accusations of others’ conduct, Washington temporarily left him in command at the front while the commander first placed the two nearby Connecticut brigades in position along a hedgerow fence running perpendicular to the road, and then galloped off to immediately bring up the remaining entirety of the army.

"Our detachment formed directly in front of the artillery, as a covering party, so far below on the declivity of the hill that the pieces could play over our heads. And here we waited the approach of the enemy, should he see fit to attack us. By this time the British had come in contact with the New England forces at the fence, when a sharp conflict ensued. These troops maintained their ground, till the whole force of the enemy that could be brought to bear had charged upon them through the fence, and after being overpowered by numbers and the platoon officers had given orders for the several platoons to leave the field. They had to force them to retreat, so eager were they to be revenged on the invaders of their country and rights."

The engagement at the hedgerow shortly after noon of that torturously long and torrid day represented some of the most vicious combat of the war. American artillery on the heights in rear of the fence blasted the fields and wetlands in front of the Connecticut and Rhode Island infantry with solid shot and canister. Nevertheless, the British infantry displayed remarkable discipline, sweltering in their red wool regimental coats and tall black neck stocks. Supported by their own artillery in rear and assisted by their impetuous light horsemen whenever allowed by terrain, the troops repeatedly drove on through the marshes and sizzling sandy fields to gain the Americans' heights. Perhaps spurred on by his chagrin, Lee finally began to perform. The positions were well chosen, the troops well managed. In spite of their sterling performance, though, the number of Continentals was simply too small to withstand the successively expanding enemy assaults. With Washington’s main force moving at a furious pace to reach the front, Lee was nonetheless forced to slowly give ground. It was during this strategic withdrawal that a force of about 500 “picked men” was selected for a highly important and successful flank movement around the right of the British battle line. Private Martin and likely his company messmate Jonathan Preston were among the platoon of the 8th Connecticut chosen:

"Before the cannonade had commenced, a part of the right wing of the British army had advanced across a low meadow and brook and occupied an orchard on our left... We had a four-pounder on the left of our pieces which kept a constant fire upon the enemy during the whole contest. After the British artillery had fallen back and the cannonade had mostly ceased in this quarter, and our detachment had an opportunity to look about us, Colonel Cilly of the New Hampshire Line, who was attached to our detachment, passed along in front of our line, inquiring of General Varnum’s men, who were the Connecticut and Rhode Island men belonging to our command. We answered, 'Here we are.' … 'Ah!' said he, 'you are the boys I want to assist in driving those rascals from yon orchard.' … We instantly marched towards the enemy’s right wing, which was in the orchard, and kept concealed from them as long as possible by keeping behind the bushes. When we could no longer keep ourselves concealed, we marched into the open fields and formed our line.

As I passed through the orchard I saw a number of the enemy lying under the trees, killed by our fieldpiece, mentioned before. We overtook the enemy just as they were entering upon the meadow, which was rather bushy. When within about five rods of the rear of the retreating foe, I could distinguish everything about them. They were retreating in line, though in some disorder. I singled out a man and took my aim directly between his shoulders. (They were divested of their packs.) He was a good mark, being a broad-shouldered fellow. What became of him I know not; the fire and smoke hid him from my sight. One thing I know, that is, I took as deliberate aim at him as ever I did at any game in my life. But, after all, I hope I did not kill him, although I intended to at the time."

While Martin knew that this particular enemy unit “were Scotch troops”, he likely was unaware that the 500 New England picked men were engaged with the vaunted 42nd Royal Highland Regiment, the celebrated Black Watch. Excepting for some brief confusion at the battle of Harlem Heights in 1776, this elite royal regiment prided itself in never having been reversed by an enemy. But, here, in this sweltering New Jersey orchard, the Black Watch was thoroughly routed by an ad hoc force of Connecticut, New Hampshire and Rhode Island Continentals. Perhaps nowhere else on the torrid field of Monmouth would the score be better settled by the vengeful Americans than in this small unit action at the orchard. The stage was now finally set for the commander-in-chief to lead the main portion of the army in expanding and making conclusive this advantage.

Following the withdrawal of Lee’s advanced line, the British pressure continued to build, both in numbers and ardor. In response, however, the Continental artillery fire significantly intensified, blasting the enemy front with round after round of shot and canister. It was as result of this vicious encounter that the highest-ranking British casualty at Monmouth was sustained, Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Monckton, commanding the 2nd Battalion of Grenadiers, being mortally wounded. This obstinate Continental defense caused Sir Henry Clinton to array a line of British guns on the opposite heights, the result being an artillery duel that continued for several hours of the waning afternoon. As Washington aligned and brought forward the 8,000 Continental infantry yet unengaged, the British and American gunners pounded each other’s positions in what was described as a “cannonade… heavier than was ever known in the field in America.” Now, surveying the rank upon rank and line upon line array of what had been contemptuously regarded as “country clowns”, Sir Henry Clinton concluded that the “rebel” forces and position made them too strong for frontal attack and impervious to a flank assault. To bring his conclusion to certainty, a Continental brigade with artillery support suddenly appeared on high ground to the south and effectively deployed enfilading fire on the British left flank. As an immediate result, Clinton terminated the bombardment from his lines, withdrawing his artillery.

This removal of the guns left the British infantry lines particularly susceptible to both frontal and flank attacks, this being the near immediate result. Another ad hoc force of “picked men” harried the rear of the suddenly retreating British 3rd Brigade, followed by an assault of several Pennsylvania regiments upon the 1st Division. The hedgerow area was again the center of vicious combat as Anthony Wayne led his Pennsylvanians in an attack upon the vaunted British Grenadiers. Again, the King’s troops were forced to a hurried retreat. As the tables were turned and many red-coated troops were suddenly “on the run”, the terrible 96-degree air temperature and compounding humidity continued to add to the toll. Substantial numbers of men on both sides dropped in the sandy roads and baking fields. Some units suffered as many fatal losses to heat stroke as to enemy fire. To both the retreating British and the joyous but exhausted Continentals, no other sunset likely ever seemed as long in coming.

As the daylight began to fade and the bulk of the engaged British forces regrouped at the village of Freehold, it was discovered that two units had been pinned down and stranded in the hellish blasted ground of the lowlands in front of the hedgerow heights. As portrayed in Clinton’s memoirs, it was the 33rd Regiment of Foot that was sent forward again to assist in extricating their comrades, thereby becoming one of the very last British units to retire from the field:

"… from my intentions not being properly understood, or some other cause, all the troops had quitted it soon after me except the First Battalion of grenadiers… and the enemy began to repass the bridge in great force. Wherefore on my return I found this brave corps losing men very fast; and, as I was looking about me in search of other troops to call to their support… I perceived the Thirty-third Regiment.… unexpectedly clearing the wood and marching in column toward the enemy. The First Grenadiers, on this, advanced also on their side; and, both pushing together up to the enemy in order to stop the cannonade from a farm on the hill, their [the enemy] troops did not wait the shock, but instantly quitted and retired again across the bridge. The First Grenadiers and Thirty-third then put themselves as much under cover as possible (by shouldering the hill on their left) until the light corps, whose usual gallantry and impetuosity had engaged them to far forward, were returned."

The complete movements and actions of the 33rd Regiment during that day are quite difficult to document. In fact, Monmouth is one of the most challenging major engagements of the war from which to develop a precisely accurate portrayal. That the regiment was significantly engaged and conspicuous in its activities, though, is quite clearly supported by an excerpt of a letter from Lieutenant David Griffith of the 3rd Virginia Regiment to his wife, dated July 2:

"the troops that were beaten on Sunday were the flying army of the enemy, consisting of all their grenadiers and light infantry, a brigade of guards, and the 33rd Regiment. These were the troops that beat us at Brandywine."

To this day, historians debate the outcome of the Battle of Monmouth, many contending it to have been a draw, with little military but much political impact. In considering such an interpretation, however, three points are inarguable. First, while the Continental troops spent the night in battle line formation, with Washington gaining a few hours sleep wrapped in his cloak under a tree, the entire British column slipped away soundlessly and forced its march toward the waiting fleet at Sandy Hook. Second, and without precedent in this war, the British army left its dead and many of its wounded upon the field, many Continentals spending much of the following day on burial detail. Finally, Monmouth was the last major engagement in the north as British focus shifted to the Carolinas and Virginia. Slightly more than one year later, however, some of the same Continentals who had fought at Monmouth perfectly executed a remarkably difficult midnight surprise attack on and capture of the entire British garrison of Stony Point on New York’s Hudson River. From the date of Monmouth, very few of His Majesty’s officers and rank and file would ever refer again to the Continentals as “country clowns.” The score had been settled.

A Trophy Taken

"… I heard firing of cannon and small arms at Freehold. I rode immediately that way, came on the battleground, was near the center of our troops that were engaged. The balls flew thick around me. I was there when the enemy advanced with charged bayonets and Colonel Monckton, their commander, was killed. …The enemy then retreated precipitately, throwing away many of their guns. I was, I believe, the foremost in following, got as many of their guns as I could conveniently manage on my horse, with their bayonets fixed upon them. Gave them to the soldiers as they stood in rank. They threw away their French pieces, preferring the British."

Thus New Jersey militiaman William Lloyd, a local resident, described a portion of his experiences on June 28, 1778. His description of Continental troops exchanging their French muskets for captured British ones has particular relevance. For, whether on the day of the battle or during the day following, and under whatever circumstances, Private Jonathan Preston of the 8th Connecticut Regiment became the new owner of the Short Land musket of the 33rd Regiment of Foot carried to that field by the British infantryman known only by the arm’s rack numbers … “L/51.” Let us now examine this uniquely provenanced musket.

Lock and lock plate

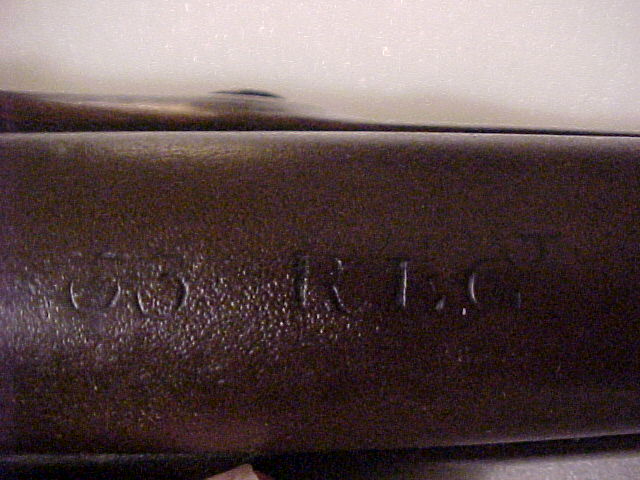

As previously mentioned, the weapon is an example of the so-called “first pattern” Short Land British musket adopted for use by all infantry regiments in 1768, with issuance beginning the following year. The primary revisions from the traditional Long Land model now seen in this new pattern included a barrel reduced from 46 to 42 inches, a brass side plate modified from convex to flat, the elimination of the top screw from the butt plate tang, and removal of decorative carving around the lock. Standard to this weapon’s production, the lock is engraved with “TOWER” at the rear, and with the royal crown and “GR” motif appearing in front of the cock. All standard inspection, proofing and subcontractors’ marks also appear on lock, barrel, furniture and in the stock. To signify its unit issuance, there is engraved atop the barrel in an area extending over the front edge of the lock plate “33 REGt.” The last of its original British markings are the so-called rack numbers engraved into the brass escutcheon plate, typically intended to indicate the company and number of the man to whom the musket was issued. The “L/51” of this example is strongly believed to indicate the Light Infantry company of the 33rd, the arm being issued to the fifty-first man on that company’s roll.

Tower Marking

Crown and GR [George Rex]

33rd Regt

Rack Number L/51

Likely within the first few weeks following his acquiring the musket, Private Preston — and/or Joseph Plumb Martin, a developing artist himself — added the truly remarkable additional identification markings, thoroughly “Americanizing” the previous King’s arm. Into the flat face of the serpentine side-plate, he incised his full name… “JONATHAN prESTON” …surrounding that with a delicate foliated vine motif. On the somewhat more challenging curved face of the escutcheon plate, he added below the British rack marks his own unit identification… “Cr” …the abbreviation for “Connecticut Regiment” that appears on the well known series of regimental buttons of 1781, but that assuredly was in use for marking accouterments prior to that time. An interesting aside is that, from these two added markings, it is evident that Preston was unfamiliar, or at least less familiar, with a capital “R”, using a lower-case letter in both instances.

JONATHAN

prESTON

Continuing the memorialized markings of his Monmouth trophy, Preston deeply carved… “1778” …into the reverse butt face. Since June 28 was the one and only day of that year that the 33rd Regiment of Foot and the 8th Connecticut Regiment were in anywhere near close proximity, it is this piece of “data” that clearly ties the musket to Monmouth.

1778 carved in the buttface

Most notably important to the correct and full documentation of the musket is Preston’s seemingly cryptic carving on the obverse stock butt face … “IP//”. At first apparently incomprehensible, it is this marking that is key. First, it was very common in the mid- to late-18th century that the capital letter “J” was formed as a capital “I”, often, as in this case, with a horizontal line at the midpoint. This is seen in earlier Long Land “Brown Bess” muskets from the lock maker named Jordan, the lock plates being engraved “IORDAN.” Similarly, many embroidery samplers of the period have no “J”, the “I” being the substituted motif. Thus, the first two letters of this butt stock carving are meant as “JP” for, of course, Jonathan Preston. But, what to make of the two slashes? Ironically, these are the ultimate verification key. Research with the National Archives’ index of the Compiled Service Records of the Revolution demonstrated that four men of the name “Jonathan Preston” served in the war. Only one of these four served in the Connecticut Line. But, to assure that no doubt could exist as to the identification with Jonathan of the 8th Connecticut, all four were researched. The remarkable point that emerged is that the Connecticut Jonathan is the one and only of the four whose father was also named Jonathan. Our man, that is, was a “junior, or, as he wrote it in the butt face carving, “the second.” Without the slightest doubt, the man who so clearly and fully “Americanized” this musket was Private Jonathan Preston of the 8th Connecticut Regiment.

IP// carved in the obverse butt face

One last question that might be asked regarding the “IP//” carving is… why upside-down? Notably, other muskets with carved initials or datings have been seen to have this same characteristic, an upside-down positioning when on the stock's obverse butt face. Perhaps the best known of these is the superb Wilson Long Land musket at the West Point Museum with “N-Y/1. REG” branded into the obverse butt surface in the upside-down position. A bit of thought resolved this minor riddle. If the carver is working with the musket across his lap, holding up the weight of the barrel in his left arm and carving with his right hand, it is impossible to maintain this working arrangement with the obverse butt face. Unless assisted by someone else and working on a table, the only viable approach for a right-handed craftsman is to carve the obverse butt in an upside-down position.

Precisely how Preston acquired the 33rd Regiment of Foot musket will never be fully known. He might have actually disarmed a prisoner, or recovered the weapon from a wounded or dead member of the regiment. The loss report for the 33rd from Monmouth does survive, but it is not particularly detailed. Perhaps more likely, Preston may well have simply picked up the musket that had been dropped by its original owner during a retreat or while in a “tight spot”, or found it while working on burial detail on June 29. Lastly, he could have been among the Continentals whom militiaman Lloyd supplied with a replacement arm.

Regardless of the specific details of how the musket came to Private Preston’s hands, the extent of its “story” that we are able to reconstruct is truly remarkable. As most students and collectors would be aware, identifiable and researchable long arms are far more common for the period of the Civil War than for the Revolution. An immensely greater number of men in service, a measurably higher literacy rate, and the lesser period for attrition of the surviving specimens all have contributed to this differential. While few collectors have never seen an identified Civil War musket, very, very few examples of identified Continental Army long arms have survived for study. Beyond an identification of the bearer of the arm, a unit identification and fully supportable documentation of a musket captured from the enemy at a well known engagement are literally unheard of. Taken together, such unparalleled provenance strikingly illustrates how dramatically an object of “material culture” is, more so than any other resource, capable of breathing life into history, and how dramatically such an object can become as informative as any archival document. These additional engagement-specific and “trophy” characteristics of the Jonathan Preston musket make it truly unique.

Return to In Their Own Words